Chillies: Hot but very Cool

- May 12, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: May 14, 2020

World over, chillies (or chilli peppers) are used for food flavouring. Though most chillies are hot, there are some (for example, bell peppers or ‘capsicum’ as we know them better in India) that have very less to no heat at all.

So why are chillies different in their heat levels?

It is to do with their capsaicin content.

If you have felt a warm, tingling or burning sensation (along with an urge to cry) on eating something spicy-hot, you have definitely felt the effects of capsaicin. Chillies get their heat from capsaicin and the more capsaicin a chilli type has, the hotter it will be.

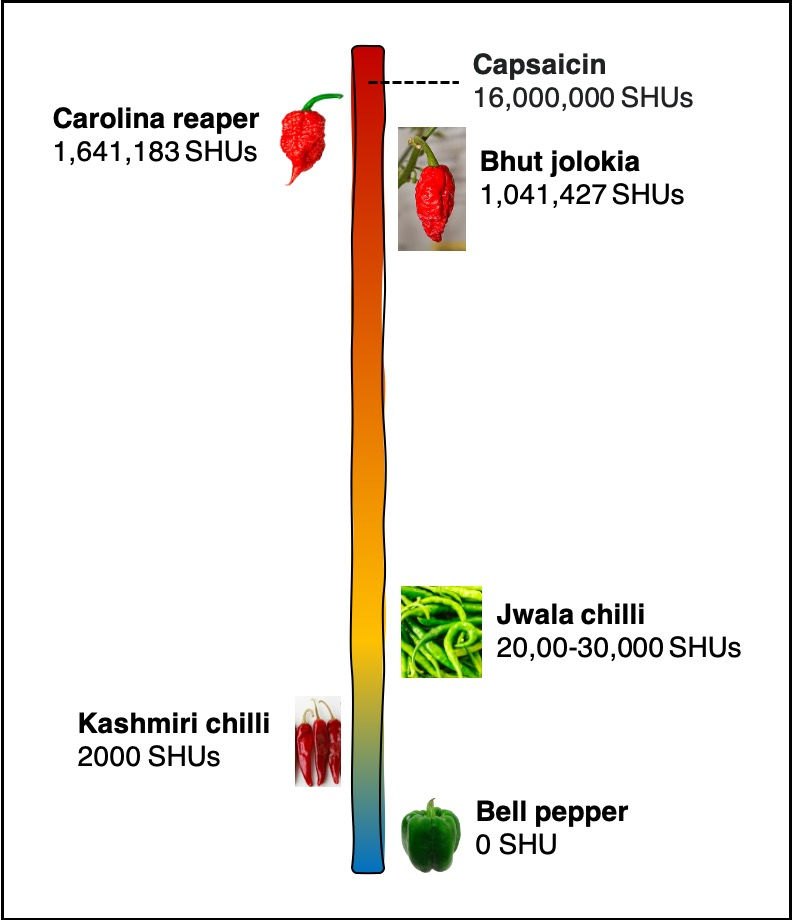

There is even a scale to measure the heat level of chillies.

In 1912, Wilbur Scoville invented the 'Scoville Scale', where he used human subjects to test chilli solutions of different intensities. The solutions were diluted in steps and tested each time until the burning sensation completely disappeared. More the dilutions needed to reach this endpoint, higher up the chilli was on the Scoville scale. The 'Scoville Heat Units' (SHU) have since been used to indicate a chilli's heat level. With advance in technology, human testers are no more needed and methods like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can directly measure the capsaicin content in chillies.

Bell pepper, with 0 SHU is at the bottom of the scale while Carolina reaper, with 1.6 million SHUs is at the top. With chillies being so important in Indian cuisine, can India be far behind? Bhut jolokia (ghost pepper) found in some of the northeastern states of India is at 1.04 million SHUs. Jwala, a commonly used variety in India, is at 20,000 - 30,000 SHUs while Kashmiri chillies, used primarily for their bright red colour, are at 2000 SHUs. Pure capsaicin stands at 16 million SHUs.

When you eat chillies, capsaicin binds to pain receptors called TRPV1 on neurons. The activated neurons transmit this signal to your brain, which releases certain chemicals and you experience pain.

Depending on the capsaicin concentration, the pain felt can vary from mild "Huh, that's nothing!" to burning "My mouth is on fire!!!". So powerful is capsaicin in causing pain that it is the main component of pepper sprays used for self-defense.

Interestingly, TRPV1 receptors are also activated in response to high temperature. So if you are eating a bhut jolokia for breakfast (do not try this at home), you should definitely avoid hot tea after that as it will only intensify the pain. If somehow you do pair up the two, better soothe yourself with a glass of milk. Capsaicin dissolves in fat but not water. Hence, milk (which contains fat - loving casein protein) is effective in toning down a chilli kick while water will only spread the effect of capsaicin.

Repeated exposure to capsaicin for longer periods of time has the opposite effect and results in inactivation of the TRPV1 neurons.

The brain then receives reduced pain signals, leading to decrease in pain sensation. This mechanism is used by several capsaicin-containing pain-relieving (analgesic) ointments.

While we are talking about effect of capsaicin on TRPV1 neurons, it is very interesting to note that birds are unaffected by capsaicin. The TRPV1 protein of birds is very different from that of mammals. Hence, birdfeed with added chilli is often used to drive away squirrels that might otherwise feed on it. Does the chilli - eating Parrot now make sense?

An American food psychologist, Paul Rozin, thinks that eating chillies (in limit) is similar to riding a roller coaster. Though both actions are discomforting at times, both are enjoyable and we often crave for more because we know that there is no real danger associated with either.

Personally, I would still prefer eating chillies to riding roller coasters. What about you?

Sources and further reading:

Cover image: A surprised boy talking to a red chilli plant by Priya Kuriyan, for Around the World With a Chilli written by Nayan Chanda, published by Pratham Books (©Pratham Books, 2015) under a CC BY 4.0 license on StoryWeaver. Read, create and translate stories for free on www.storyweaver.org.in

The science of spiciness - Rose Eveleth (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qD0_yWgifDM)

Hot Chile Peppers on the Scoville Scale (https://www.thespruceeats.com/hot-chile-peppers-scoville-scale-1807552)

The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway (https://www.nature.com/articles/39807)

How Pepper Spray Works (https://home.howstuffworks.com/home-improvement/household-safety/pepper-spray1.htm)

Milk: Best drink to reduce burn from chili peppers (https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/06/190625133526.htm)

Hot Chili Peppers Help Unravel The Mechanism Of Pain (https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090223221232.htm)

Spice is Nice (for Birds) (http://www.thepipettepen.com/spice-is-nice-for-birds/)

On Capsaicin: Why Do We Love to Eat Hot Peppers? (https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/thoughtful-animal/on-capsaicin-why-do-we-eat-love-hot-peppers/)

Comments